|

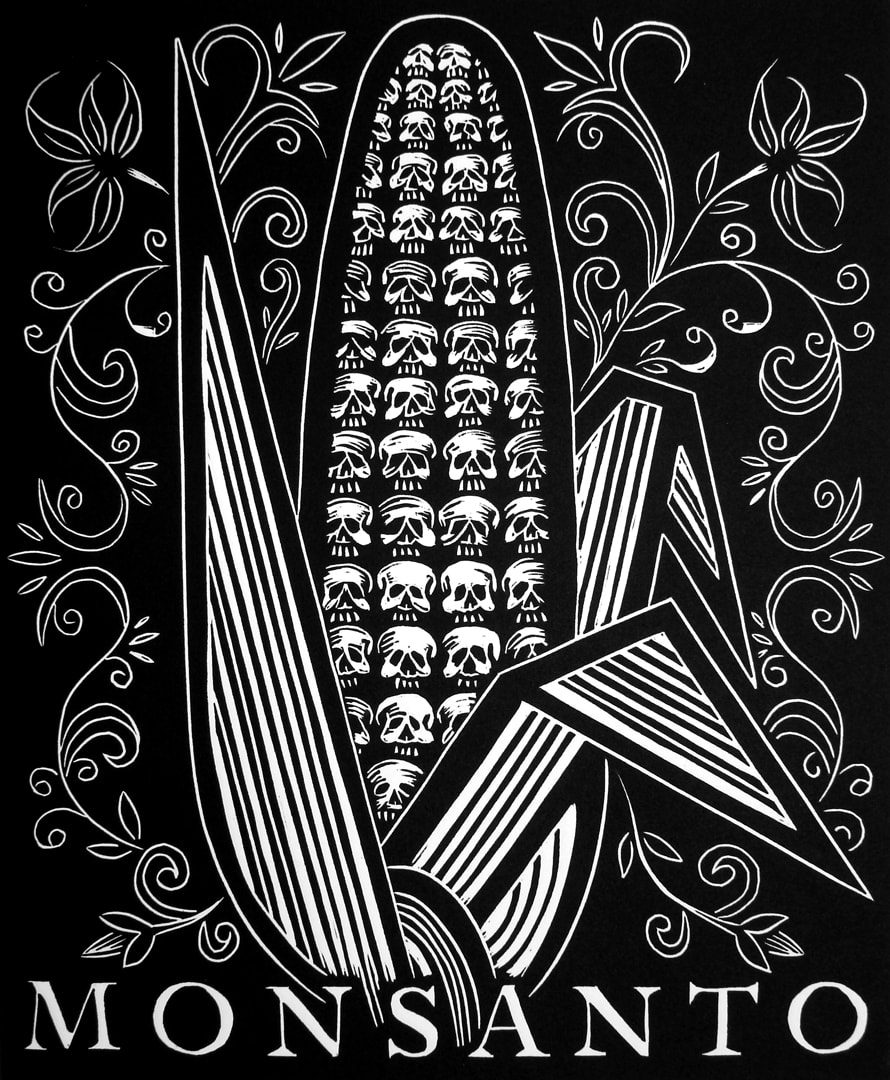

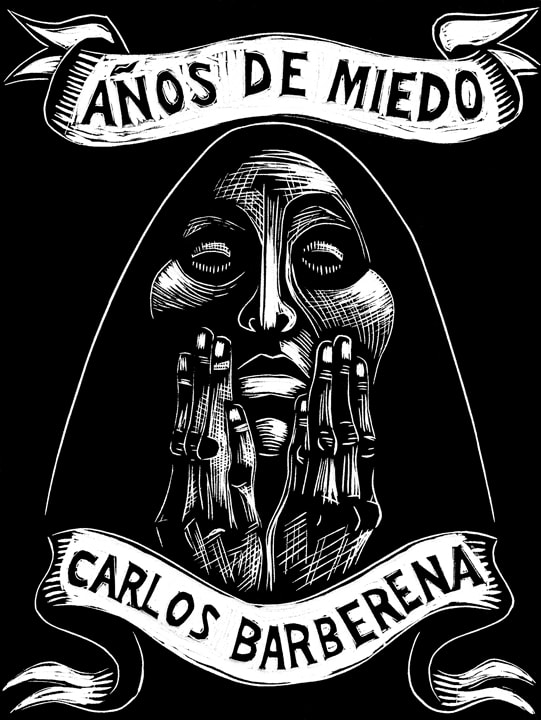

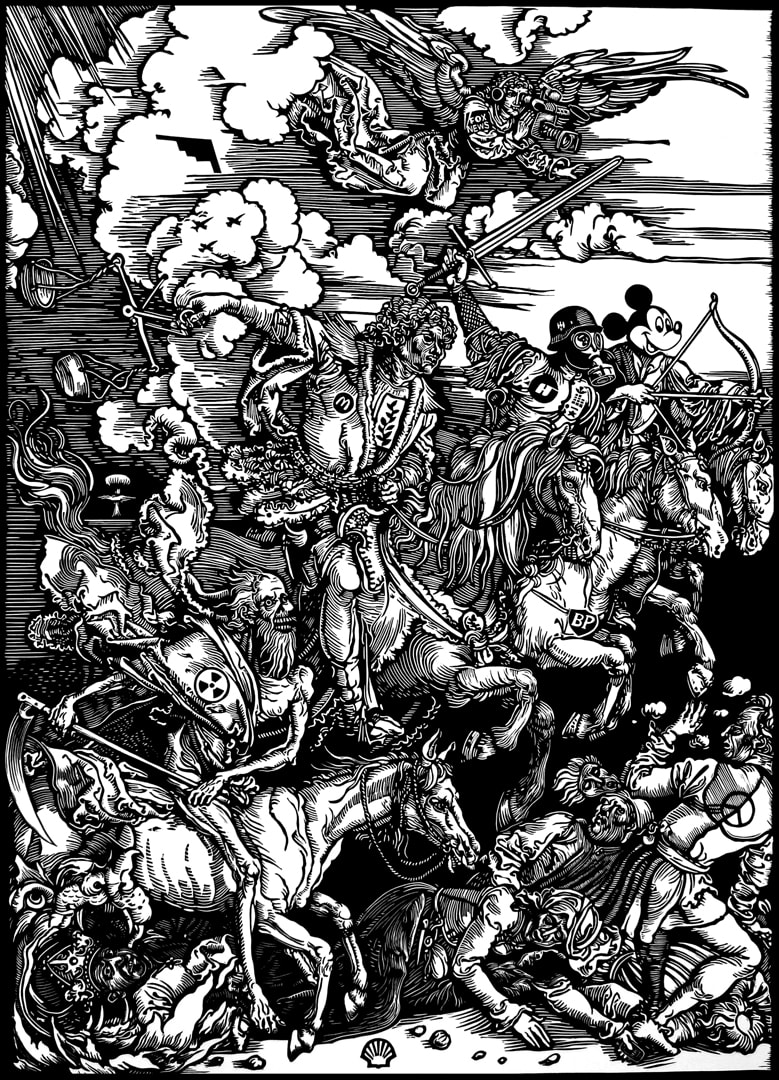

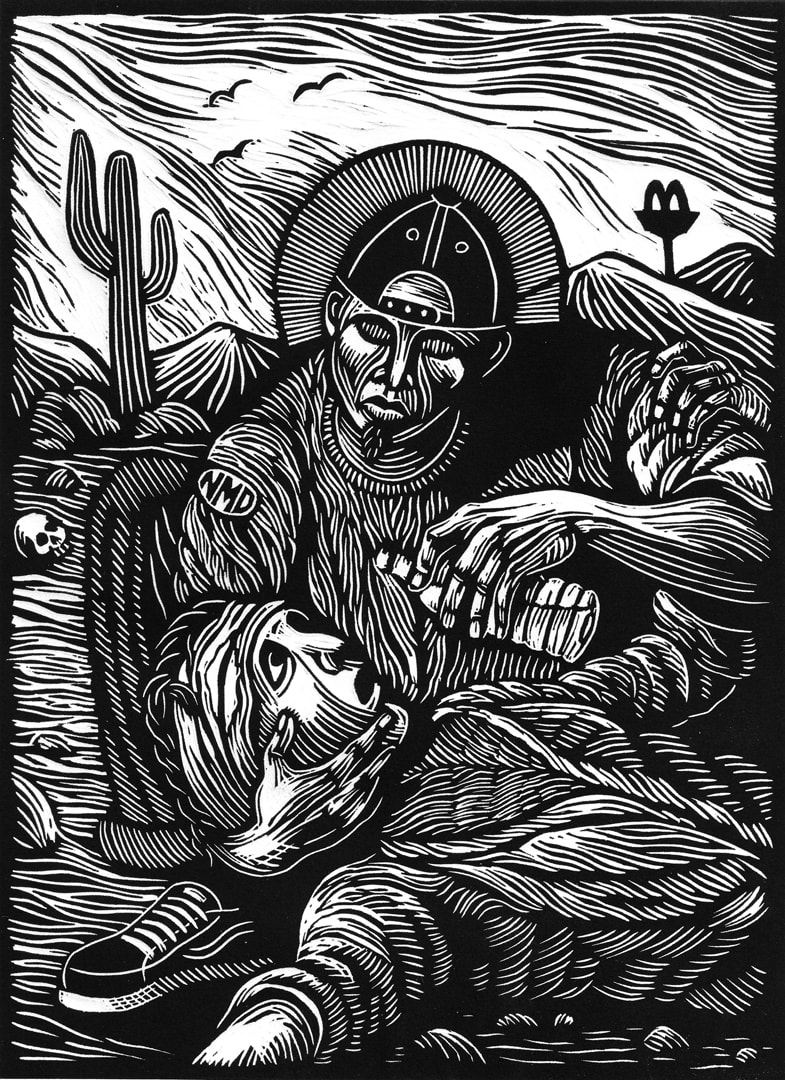

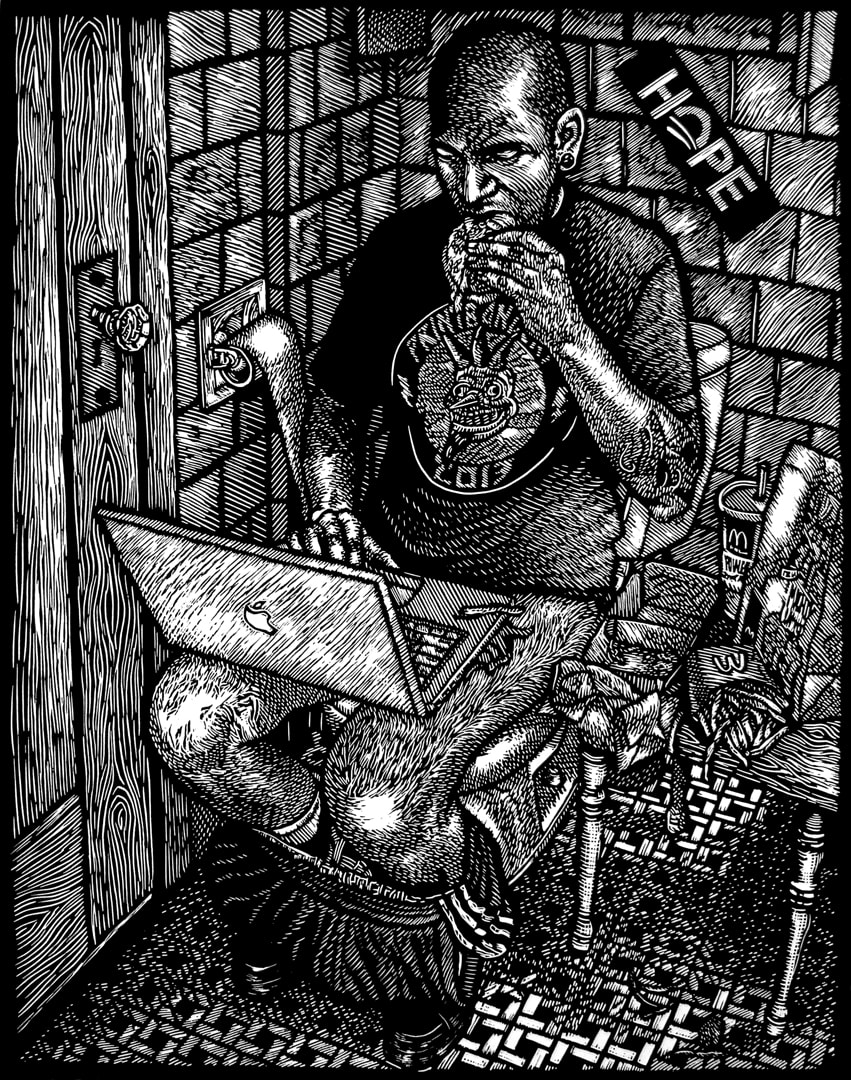

"The Prints of Carlos Barberena: A Peek of Clarity in the Darkness" By Franky Piña / El Beisman Carlos Barberena sticks the gouge in the matrix. He sculpts labyrinths, touches reliefs with his gaze. From the plowed surface a skeleton appears: two, three, four teeth. Five, six skulls. They are teeth, they are skulls and they are corn grains, but no, they’re not one or the other. Barberena carves, cuts and shreds more tiny gutters. On the surface of the linoleum sheet, a few maize leaves blossom, but it can’t be the millennial maize of Mesoamerica. That cob didn’t have the grains of death. Ceci n’est pas un maïs. Thus, it’s not a cob. It’s a linocut that shows the idea of death, but also of life. Beauty and horror co-existing. The communion of the necessary line and the precisely traced discourse. The kernels of ethics and aesthetics about to fall off this print on paper. The corncob’s trace that Barberena has printed features the Monsanto signature. The image is a source of questions: Isn’t that the transnational corporation, producing corn and other transgenic grains, that one that has bragged about creating as many grains as needed end hunger? To what extent has the Monsanto monopoly made farmworkers and agricultural business owners around the world dependent on them? To what extent are genetically modified grains contributing to the breakdown of the environment? To what extent does Monsanto have the disposition to bet exclusively on profits? And to what extent do we resist progress and modernization when standing against Monsanto? In ‘Untitled (Monsanto)’ 2010 Barberena offers no answers. As a printmaker, he creates and suggests allegories. He puts out ideas and commits to technique. Barberena is an old-school printmaker: he instigates, pricks the prevailing moral and cultivates doubt. The graphic work of Carlos Barberena is an invitation to chat. His work takes us to an ancestral tradition, hence, he pushes us to start a dialogue with the works of different times. He also places the spectator in the present. And Standing before Barberena’s prints, a feeling of awe is inevitable, as well as the many questions that his works give way to. What is the function of art during dark times? Is an anti-establishment opus worth approaching? Can the artist be considered separately from his work? And what do Barberena’s prints reveal before this paradigm? An artistic flow runs through Barberena’s veins, while indignation and longing spill. A whole pulsating system is captured in ink and reliefs on paper. Barberena: a young printmaker with the afflictions of an old man. The form in his prints is sublime. When drawing the curtain you can see many days of work with the chisel, the roulette and the etching press. Perhaps, he’s been tinkering relentlessly with the gouge in the matrix for a decade, but before that, he’d been playing with pen, paper and ink. Barberena has vigorously experimented with other mediums, but I believe it’s in printmaking where his voice has reached the highest note. The substance in Barberena’s opus is essentially linked to his biography. The creator and his work are inseparable. Together, they are one in a specific moment in time; once the piece is finished, both go their separate ways. The printwill have to stand on its own and the artist will continue carving plates. Carlos Barberena was born in Granada, a city located on the riverbank of Lake Nicaragua, in 1972. Back then, Somoza’s reign was dwindling: still reaping terror and sowing horrors at the foot of the volcano. Despite the violence in Sandino’s land, the lad grew in a bohemian atmosphere: his mother was an accomplished cross-stitcher, so much, that her finished pieces looked like paintings made of lace. His father played the guitar and used his pen to write combative union pamphlets. His great-great uncle Segundo De La Rocha was a renowned artist. Another relative Roger Pérez De La Rocha, was a militant in the avant-garde group Praxis and Carlos’ older siblings studied art. In that environment, it was a natural act for the little one to start drawing. When he turned ten, his mother came to terms with the fact that she would have another artist in the house and sent him to a popular cultural school, one of those that the Sandinista Revolution had fostered. During a drawing class, he was asked to draw a bottle. Upon finishing it, the teacher violently dismissed the child’s cubist creation and said: “You have no talent. I don’t know what you’re doing here.” Carlos left the school abruptly, not wanting to touch another pen in his life. Three years later, overnight, in one of those turns that the revolution brought, Carlos was uprooted from Granada and made Costa Rica his home. Before becoming an artist, Barberena learned to observe; and despite the fact he had been torn from his school, friends and family, he learned how to deal with pain. In Costa Rica, he went back to the pen and the brushes; estrangement and melancholy started to spill over his art. The pieces were colorful back then, but he always left a hidden message amid the tones and the lines. On one hand, he was trying to push out the baggage he had been carrying for years, and on the other, he was anxious to rescue his indigenous roots with its lakes and volcanoes, and redeem the Nicaraguan immigrant that cut sugarcane and picked coffee beans in Costa Rica. He recognizes himself as self-taught artist and wants to visually devour the world. He visits galleries and museums: he observes, admires and tries to discern the parts of what he sees. Before the easel, he starts transforming his paintings and moves away from the baroque. As a precocious painter, Barberena starts to sell his work and lives from it since he was 18. On a youthful whim perhaps, he signs a contract with a gallery and they buy everything he creates. Ten years of his life dedicated to cultivating the technique, reaping some financial freedom to undertake his most visceral projects. He reads Luis Ferrero, Jose Marti and César Vallejo. He comes to know the works of the masters: Pablo Picasso, Rufino Tamayo, Käthe Kollwitz and Oswaldo Guayasamín. He’s captivated by the latter’s art, philosophy and commitment. In body and work Barberena leans towards that road: to take sides with the voiceless. This is when Barberena’s palette starts dismissing the bright colors and earth tones begin to show up. In 1993, Barberena returned to Granada. He lived and mounted exhibitions in both countries. For fifteen years he devoted himself to his art, and started exploring with different media. Central America was changing its political landscape; several revolutionary movements were coming to a close, but a cycle of violence was beginning. The world started to turn under the slogan of a new world order. And to capture, as an artist, all this new chaos, he resorted to the camera, the manipulation of color, the photo-transfer, sculpture, intervention, and even creating installations. While experimenting with new media, he approached the themes of immigration, dishonest politicians, the clergy’s abuse, the treatment of Abu-Ghraib and Guantanamo’s inmates, to name a few. In this search to understand his times, Barberena created a significant body of work. Despite exhibiting in avant-garde galleries such as Praxis, in Managua, or in Costa Rica’s National Gallery, Barberena’s creative flame started to suffocate. No matter how much he created and innovated, his anti-establishment work would not have access to the galleries and museums he wanted to exhibit in. Just like the galleries in Central America, the type of work that sells in the art market continues to be ornamental, and sometimes functional. What woke up Barberena from his lethargy was coming in contact with José Guadalupe Posada’s oeuvre. In 2007, he came to know the prints of the maestro during an exhibition in Mexico City. By then, he had been invited to participate in an artistic residence to specialize in etching, but the instructors had gone on strike. He did not work on etching, but lithography. The one-month residency was reduced to a week and a half. Wandering in Mexico City he stumbled upon Posada’s exhibition. ‘That was a blow’, he told me. ‘To see all his political and satirical work impacted me profoundly. I was overwhelmed by the need to work with that force, that dark humor that exists in his work.’ His perspective on printmaking expanded because ‘it is a more democratic art, more of ‘the people’ since you can print almost on any surface: notebooks, songbooks, match boxes...” Barberena had gained experience as a printmaker: in 2002, the German artist Wolfgang Hunecke had invited him to participate in an intaglio workshop with etching, aquatint, and drypoint at Casa de los Tres Mundos. At the same time he discovers Posada’s work, he starts his move to the United States. In Chicago, he hangs up the brush and quits painting. He dives fully into printmaking. Planning to reinvent himself, Barberena revisits his previous work and, as a warm up on the linoleum block certain iconography that he had explored in painting reappears: the apple as an allegory of sexuality, feminine nudes, the umbrella, the moon, the Momotombo . . . from that retrospect, he decides to work in the series Years of Fear (2008-2009). It is born from an exhibit he had done in Nicaragua in 2000 and had wanted to take to war-torn places, but due to the great scale and lack of resources, it was not possible to make it happen. Years of Fear was an homage to war victims and its sequels. One decade later, he returned to the same concept, but now he poured it in linocuts and exhibited both in Managua and Chicago. Upon observing the Years of Fear series, it’s impossible to avoid seeing the influence on Barberena of three masters: Guayasamín’s La edad de la ira (The Age of Anger); Käthe Kollwitz’, War (Krieg), and Los desastres de la guerra, de Francisco Goya. From the latter, we know he printed a series of 82 etchings registering a vision of Spain’s National Liberation War against Napoleon’s troops. Goya was 62 years old back then and deaf: in his very personal vision and with great mastery, he not only captures the devastation of war, but also the horror experienced by the victims and the heartlessness of the victimizer. The writer, pacifist and graphic artist Käthe Kollwitz, captures the dark side of humanity in her series Krieg (1923). The force of her drawings gave expression to the suffering of men and women that survived World War I. In The Age of Anger, Guayasamín painted a series of 150 notable works, executed between 1961 and 1990 and attempted to show the violence human beings are capable of inflicting on other human beings. Guayasamín painted, not without anger, faces, hands, crying women, mutilation. The faces and limbs scream of the pain, despair and uncertainty of those who barely survive at the bottom of the social scale. Barberena’s prints try to capture the tragedy of the war in Nicaragua. He still lived through the last stage of Anastasio Somoza’s dictatorship at the end of the 70s. Despite being very young, he also lived through the triumph of the Sandinista Revolution and saw how the laurels of victory started wilting, until he had to leave Nicaragua. From Costa Rica, he observed and lived the refugee tragedy: ostracism, separation, racism, solitude, hunger and thirst for justice. Despite the exile, his source of ideas didn’t dry up. He continued believing in the philosophy of Augusto César Sandino: to be anti-imperialist, resist and become a free man. From that search of freedom, Barberena built his works. Years of Fear is a series of expressionists recordings that display the ease of a budding printmaker that matures print by print and exposes an amalgam of raw emotions. Each of the 25 relief prints is a war testimony. Together, they are the reflection of many, concentrated on the prostrate gaze in front of the mirror. The drama of each piece is not less than that suffered in a war, any way. In the matrixes, Barberena’s gouge carves the hunger, agony, weeping, innocence, maternity, torture, migrants, the orphan girl, the political prisoner and the fatally wounded. His rough creases conceived reliefs that punch the print’s and the spectators’ faces. If reality is incapable of moving us, art should. Of the 25 pieces that comprise Years of Fear, there is one that distresses me more than the others: ‘Anguish’. It’s the image of a woman traced with simple creases on the linoleum sheet. It seems as if she’s looking at us, but obviously not. Her gaze is fixed on something else: perhaps in the remote place where her partner, brother or daughter lies. It’s the face of despair and absence. What happened to that woman was not of her choosing. That woman lives purging the misfortune of being born without privilege. She’s brought her calloused hands to her face to silence the scream of consternation and loss. Despite her misfortune and misery, the woman remains firm. And although life is cut short or continues after the war, that woman continues to be a beacon of hope. This woman-mother, woman-sister, woman-friend is the archetype of liberty, kindness and the human condition. If we separate this print from the series of war pieces, this woman could well personify the face of any of the Plaza de Mayo grandmothers, or a Palestinian student, or an immigrant woman from Bangladesh or Saudi Arabia, an activist in Ferguson, Missouri or a mother from Ayotzinapa. Beyond his meticulous execution, ‘Anguish’ transcends time, crosses borders and rises above nationalism. After Years of Fear, Barberena reinvented himself once again and started a dialogue with the classics. There is respect in the form and irreverence in the interpretation. He chose known works and made artistic interventions. You could call them homages, or even, anti-propaganda jams. I think this series displays at least two new features in Barberena’s work. One: it breaks the solemnity of his previous work. Now he resorts to satire, that which Posada impressed on him. He starts looking at the world with irony, humor, but always through the biting critique. Upon exhibiting Years of Fear in Chicago, in a way, Barberena brought to these streets the casualties of war, first as a result of U.S. support to Central American dictatorships; and afterwards, by the embargo and sponsoring of the counter-revolution. But Barberena was already creating from the bed of neo-liberalism, Milton Friedman’s chapel and his acolytes (the Chicago Boys). So Barberena, with his chisel and sarcasm, starts to capture the cultural contradictions and havoc of capitalism in his own silo. So, in a way, he starts incorporating into his work, his experience in Chicago. This series was titled Master Prints (2009-2014). Two: he learned the impact of propaganda in art, while Barberena widening his studies on master printmakers, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). I assume he studied this artist of German Renaissance. Dürer was a modern artist; he surrounded himself by the intellectuals of his time, he knew how to take advantage of the printing press and used it as much to diffuse his work, as to spread the Christian doctrine with his religious images. He was one of the first to have a clear conscience on the artist’s role and free himself from the rules of his guild. That is why he snatched printmaking from the hands of artisans and elevated it to the heights of other arts. He was a pioneer in treating printmaking as a picture. He gave the same weight to shadows, volume, proportion and composition. He also became the predecessor of political propaganda when reproducing massively the image of Emperor Maximilian I. Dürer was interested in religion, but also in his social context. In the print ‘The Four Horsemen from the Apocalypse’ (1498), Dürer revealed people’s fear at the end of the century. People believed that the world would end in the year 1500 and the print captures the religious fear, the terror of a social crisis, as well as a critique to power. Upon working on ‘The Four Horsemen from the Apocalypse’, Barberena asks: If Dürer was alive, how would he see the world? What could be construed as a joke or hoax, is not. Barberena’s apocalyptic vision is not a visual disorder. It’s not a bold idea without being realistic, it is. It’s a reflection of the world we live in, inundated by commercial propaganda. Everything is sponsored. Everything is privatized. Profit stands above the human condition. In the representation of ‘The Four Horsemen’, and following the order according to the Bible and Dürer’s print: the first represents the Conquistador (Mickey Mouse), the second The War (sponsored by British Petroleum), the third is Starvation (featuring McDonald’s and Monsanto’s logos on its chest), and the fourth is Death (with the symbol of radioactivity and the typical scythe). The pacifist and the losers of globalization appear under the hooves of the creator’s emissaries. And all this apocalypse is being broadcast live by an Archangel from the world of Fox News. The spectacle can’t be any less real. It’s dark; war aircraft cross the sky, the atomic bomb’s mushroom has swelled once more. If we read into the work’s symbolism, perhaps we could read — with little encouragement — the current condition of the world. Corporations are the sponsors of modern democracies; the world’s educational victory has fallen under the cultural homogenization brought by Mickey Mouse and show business; hyper-consumption has taken climate change to the edge of disaster; repression and intimidation have turned into the means to break those who resist the dominating cultural uniformity. In the Master Prints series, Barberena has proven his expertise with the gouge and the etching press as a printmaker. Amid play and exercise, he’s turned around the function of propaganda. He doesn’t want the observer to buy a product, but to think and smile faced with our sad condition, and by provoking thought we can reach understanding. He knows the observer recognizes the allegories, and with the same persuasion used by propaganda the work will give way to questions. That is why his pieces have a didactic goal. These prints reflect the artist’s concerns, but he also shares them with the spectator and continues to believe that it is possible to create another world. Today, living north of the Río Grande, Barberena has completed the panorama of the immigration phenomenon with more clarity. Although he had touched on this subject both in drawings and paintings, the print now has brought us nearer to the tragedy Central Americans face when crossing México. ‘Riding the Beast’ (2012) is a fable about the time that ‘modernity’ holds tight: a migrant, that could well symbolize the present, is riding on the beast. On his back, we see his travel companions represented as skeletons. Behind, is the unmovable past and also the famous golden arches of the hamburger. Those arches that represent, anywhere in the world, the alleged triumph of capitalism above any other ideology. The facetiousness of democracy, and liberty reduced to a couple of French fries. The triumph of imageology above the individual’s well-being. That prosperity that never came... Next to the migrant, death carrying an hourglass in its hands. It’s all a matter of time. The face is unchanging. What has he seen in the parcel or barrio left behind? What did he witness along the way? He can only see with eyes wide open. He looks ahead, towards the future, but the observer can’t see anything beyond the doubt and death’s allegory. Not all is anger in Barberena. Not all is a critique. Everything is pulsing. It’s thought and poetry. In the linocut ‘Saint Pollero (Coyote)’ (2011), Carlos builds a quite emotional scene. Despite the solitude and the abandon that the immigrant falls into when crossing México and the border, s/he will always find a glimpse of faith in the other. In this case, a ‘coyote’ offering water helps the immigrant that has passed out in the middle of the desert. Perhaps it will be the last drink he takes, perhaps he will get up and continue on its way. The observer doesn’t know this. It’s not in the print. In the print we only see a compassionate gesture for the other, and that act may teach us more about love and justice than any ideology. Barberena has been creating for almost 25 years. His work has reached a solid formality that speaks of dedication and persistence. He does not believe in muses, but in hard work every single day. He has a self-portrait from 2013, ‘McShitter’, which synthesizes his formal qualities. He creates, with creases of different size, a mosaic of patterns that represent the different textures seen in a bathroom. Each texture is unique and features the materials with as much fidelity a print can allow. The technique is not the most valuable thing in this piece, that is not exempt from the dart of self-critique. For many, it may be an exaggeration, but for me it’s a faithful picture of a contemporary human being. Carlos is sitting on a toilet holding a McBook on his knees. Is he working? Is he reading the news? Is he paying bills? Is he checking out a new printmaking technique on YouTube? Is he chatting on Facebook? It’s the face of someone connected to the global village, but disconnected with itself. In the self-portrait he seems focused on the outer world while he’s biting on a Big Mac with a super-sized drink, in case he chokes. The toilet apparently offers the comfort that an office lacks. In the privacy of his bathroom, the man finds himself, reaches freedom and gives way to his pleasures, his perversions. I believe this piece wouldn’t have the same impact if the model was someone different from the artist. Satire allows him to laugh about others, but first and foremost, to laugh about himself. Finally, beyond the humor, I think the creator is aware that he may also trip and fall into the trap that a salary brings: the comfort. Carlos Barberena’s prints offer a peek of clarity, a pinch of awareness, and stimulate passion for the art of printmaking. -Translated by Carolina A. Herrera * Franky Piña. Writer and graphic designer. He has co-founded several past and present cultural and literary magazines in Chicago: Fe de erratas, zorros y erizos, Tropel and Contratiempo. He is the co-author of the book Rudy Lozano: His Life, His People (Workshop in Community Studies, 1991). Piña was also featured in Se habla español: Voces latinas en USA (Alfaguara, 2000) and Voces en el viento: Nuevas ficciones desde Chicago (Esperante, 1999). He functioned both as editor and publisher of Marcos Raya: Fetishizing the Imaginary (2004), The Art of Gabriel Villa(2007), René Arceo: Between the Instinctive and the Rational (2010), Alfonso Piloto Nieves Ruiz: Sculpture (El BéiSMan PrESs, 2014). Currently, he is the executive director of El BeiSMan and the Chair of the Encounter of Latinx Authors in Chicago.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

BANDOLERO PRESS

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed